Who doesn’t love a good ghost story during this spooky Halloween season? Here is Eagle County we have our very own infamous ghost town – Gilman. The rich history of this mining town tells a story of boom, bust, and a haunting legacy.

A Promising Beginning

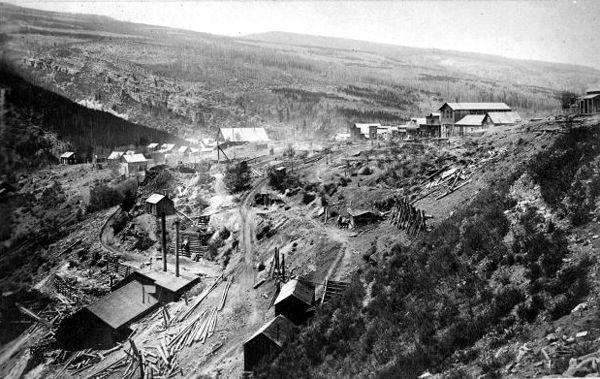

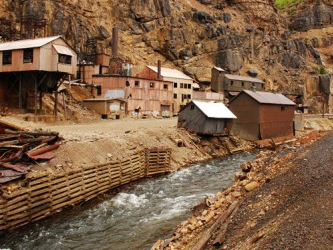

Founded in 1886 during the Colorado Silver Boom, the town later became a center of lead and zinc mining in Colorado. The mining district became the richest and most successful in Eagle County.

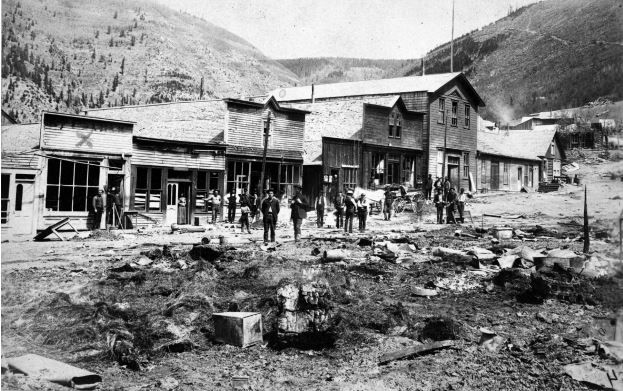

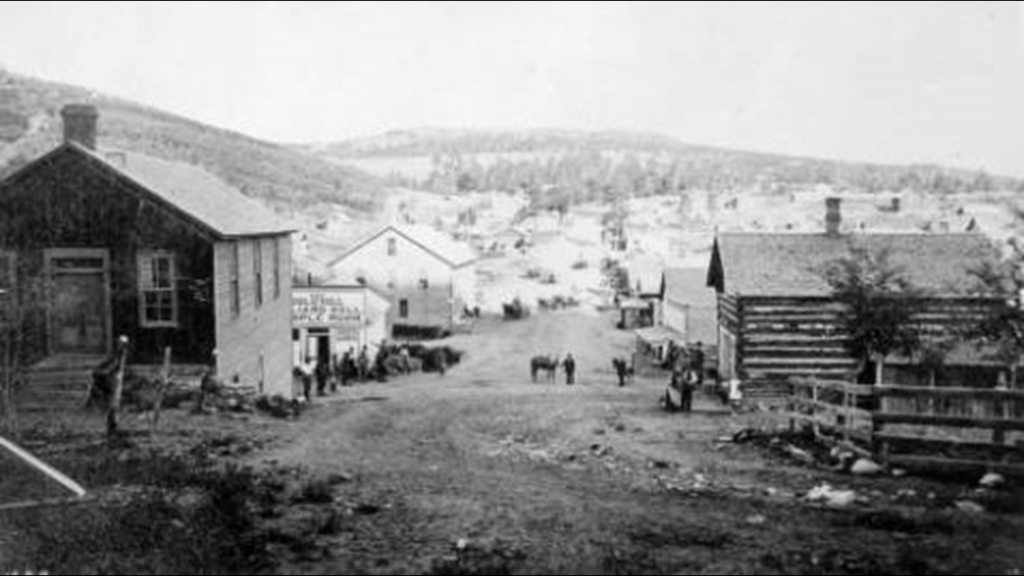

By late 1887, the fledgling town boasted a hotel, a boarding house, a general store, a billiard hall, a sampling room, a newspaper called the Gilman Enterprise, several saloons, and a population upwards of 1,000 people. Like many other mining camps, it also hosted several rowdies who might ride their horses into a saloon, shoot out the lights, and conduct acts of banditry and violence.

In 1899, Gilman was almost destroyed by a fire that took down the Iron Mask Hotel, the school, the shaft house of the Little Bell Mine, and much of the business district.

By 1900, some $8 million in silver, gold, and lead ore had been recovered on Battle Mountain. However, by this time, the area mines were no longer producing much silver and turned to mining zinc.

In 1905, The Eagle Milling and Mining Company reopened the Iron Mask Mine with a new emphasis on zinc production and installed a roaster and magnetic separator that separated the zinc minerals. In 1912, the New Jersey Zinc Company began buying up the claims and land on Battle Mountain, including the town of Gilman, and the days of independent miners came to an end.

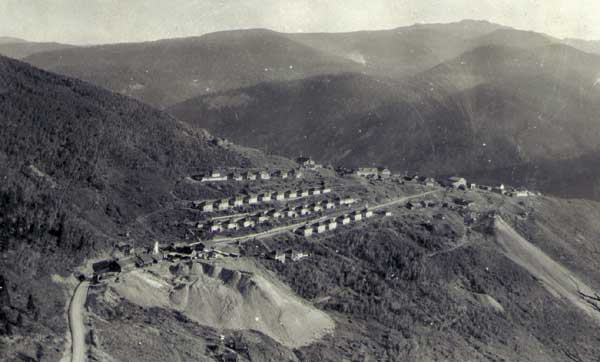

Efficiency was an essential part of Gilman’s longstanding commercial success as a company town. The company began buying and tearing down all the old cabins and, by 1919, erected dozens of uniform houses placed in rows down the hill from the shaft house. With black tar paper roofs and gray paint, these utilitarian houses were well insulated and had electricity and hot water.

The company maintained total ownership of Gilman, including the housing, school building, post office property, and all of the town’s retail space. The company built a two-story clubhouse with a pool hall, basketball court, and library-lounge, that served as the hub for recreation. They also built a hospital, a general store, a dormitory, and a mess hall to accommodate 60 men.

The clubhouse often brought the whole community together for monthly dances, sing-a-longs, Hollywood movies, and holiday celebrations. Further entertainment was found during the winter when residents enjoyed sledding down the steep hillsides on cardboard, garbage can lids, coal shovels, and toboggans, sometimes to the base of Battle Mountain. Skiing was introduced to the community by Scandinavian workers in the 1920s, long before the nearby ski resorts were founded. In these early days, the skiers utilized plain wooden skis without fancy boots or bindings and made poles with broomsticks rammed through coffee can lids. The residents also enjoyed the unspoiled wilderness around Gilman for hunting, fishing, hiking, and camping.

Zinc remained the economic mainstay until 1931, when low zinc prices forced the company to switch to mining copper and silver ores. Amid the Great Depression, most industrial mining virtually ceased in Colorado, but unlike similar mechanized mines, the Eagle Mine never closed. Though the company did lay off many single employees and cut the hours and wages of remaining workers, comparatively speaking, the Eagle Mine was quite successful during this time, producing 85 percent of Colorado’s copper and 65 percent of its silver. In 1933, the company recalled many of Gilman’s laid-off workers.

But by the mid-1970s, most auto manufacturers had abandoned chrome in their vehicles, and the mine’s zinc reserves were nearly exhausted. A spike in gold and silver prices kept a much smaller operation going for a few years, but ultimately the Eagle Mine closed at the end of 1977. In December 1977, the operation laid off 154 miners after a two-week notice, with 16 remaining on the payroll. Afterward, some limited copper and silver production occurred, but that too soon ceased, and the pumps were deactivated, and the mine was allowed to flood.

In 1983, the town and its mines were sold to a Canon City businessman named Glen Miller, who planned to put the land to multiple uses, including converting mine tailings into fertilizer, creating new residential development, and the possibility of developing a ski resort. However, within a year, he sold the town to the Battle Mountain Corporation.

Disaster Strikes

Gilman became an official ghost town in the spring of 1985 when the Battle Mountain Corporation evicted its remaining residents, and the post office closed its doors forever.

After the closure of the mine and the abandonment of the town, a 235-acre area, which included eight million tons of mine waste, was designated a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Massive amounts of pollutants had been released into the ecosystem, which placed the site on the National Priorities List.

Interestingly, CBS Operations, Inc., who bought Viacom International, Inc., which owned the controlling shares of New Jersey Zinc Company, was deemed responsible for the site’s cleanup. Cleanup of the mine began in 1988 with the relocation of mine wastes and capping of the main tailings pile. According to the EPA, the network of mines included “an estimated 70 miles of underground mine tunnels”.

EPA Updates Status

In September 2021, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency on Tuesday issued the removal of part of the Eagle Mine Superfund site in Minturn from the National Priorities List (NPL). The deletion of Operable Unit 2 at the Eagle Mine Superfund site reflects the significant progress that has been made to secure the site and protect human health and the environment. Therefore, EPA and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) have determined that no further cleanup response is necessary at OU2 of the site.

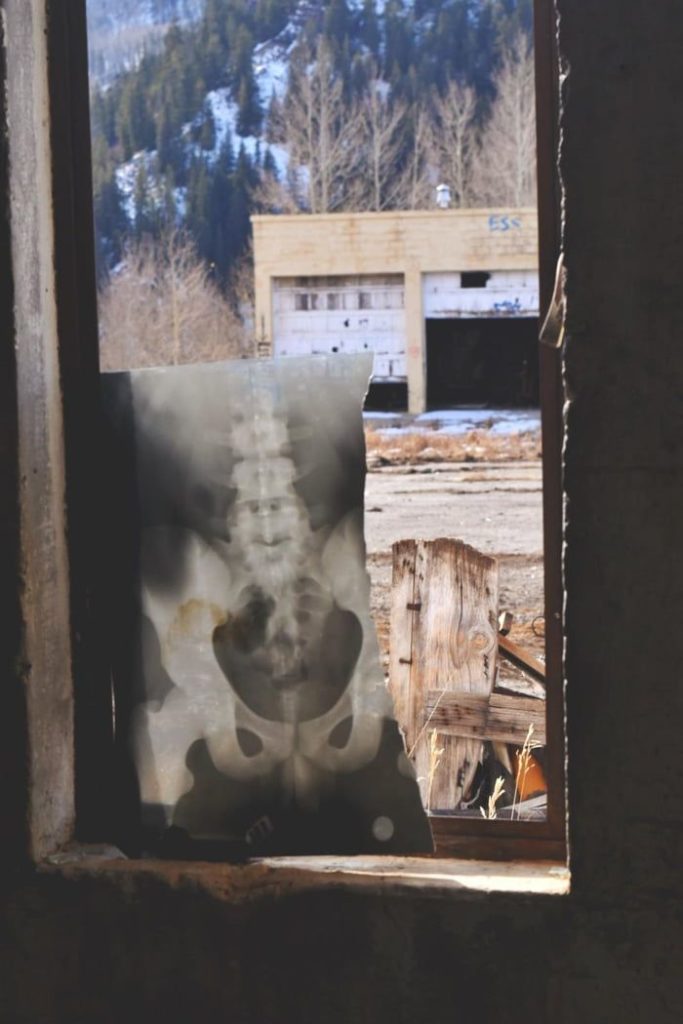

Despite the new designation, the future of Gilman is still unclear. “No Trespassing” signs hang on the closed gates, and more signs are posted warning trespassers of “Hidden and Visible Dangers” and the “Risk of Injury or Death.” However, in years past, many have ventured onto the property, despite the warnings. This is evidenced by the amount of graffiti on the buildings and photographs taken by trespassers. Inside the buildings, x-rays are strewn about the old hospital; mine records remain in the offices, furniture and appliances sit rusting and deteriorating in the houses, and a rusty swing set and a slide still sit in the old schoolyard. Mine buildings are filled with old equipment and abandoned vehicles.

Tour tickets are now available to view the mine so book ahead: https://erwc.org/event/eagle-mine-tour/. Do not attempt to view on your own, as trespassing is strictly forbidden and violators are routinely persecuted.

Notice: No trespassing means no trespassing. The Eagle County Sheriff’s Department stepped in and now cites trespassers with a ticket and a fine. To help with the enforcement of the no-trespassing laws, the local Crime Stoppers organization rewards tipsters with as much as a $1,000 reward.